Introducing my new painting: The Gentleman (in Paris)

For those keen-eyed amongst you, particularly those reading my recent Spanish posts and my various tapas recipes, you may have noticed (as I know a couple of my regular readers did) in the background in the garden of my Marbella house stood a little easel and upon it a small canvas – from the early photos, when just a blank canvas was present, to the latter shots which showed me making some progress on the work as the balmy days of my holiday whiled onwards.

As the idea developed, and owing to the sad reality that our holiday was only 9 days long, my painting became more compelx, and when I left Marbella, the work was only half done. Luckily the canvas fit in my case (although no doubt contributed to my excess of baggage weight for which the ever unreasonable British Airways charged me a 50 euros flat penalty fee, even though my partner’s luggage was massively underweight) and I continued work in London. Be my life in London as it is – full of work and busyness, it has taken me some time to complete the painting, even though I rushed home most evenings to fit in a few hours of work.

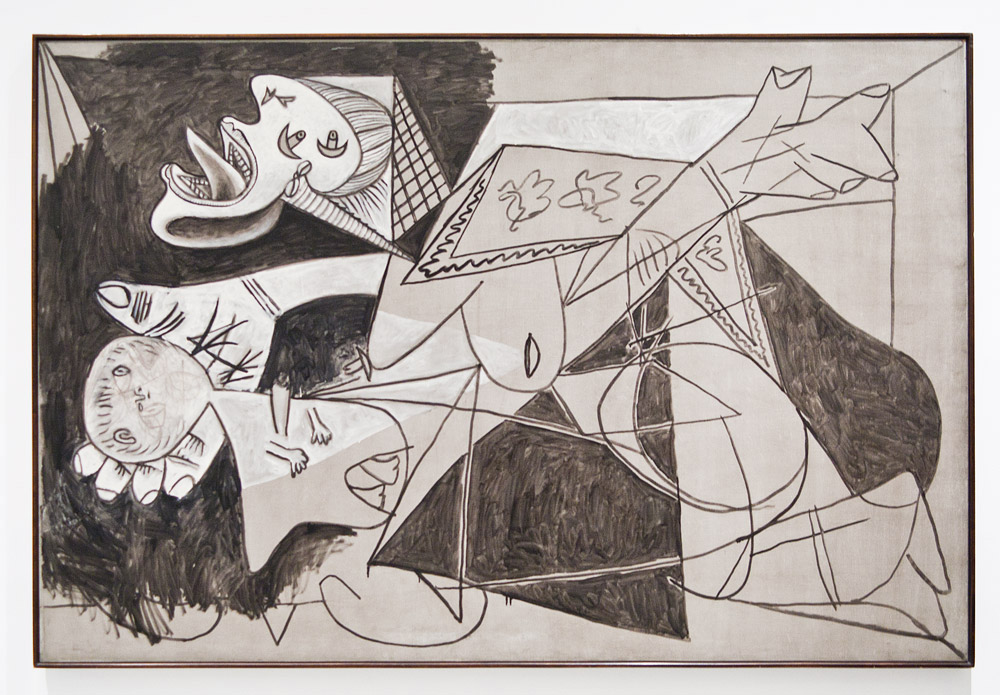

However, having had last weekend to myself, I finally managed to complete the work, a work which I now call The Gentleman (in Paris).

Inspired by the icons of a time I hold dear, a yesteryear when men were gentlemen, when to go out to dinner was a time of dressing up in a top hat and gloves, when chivalry was at the forefront of society and manners were a thing held in the highest of esteem. It was a time when in a Gentleman’s study, such as this one, a Chesterton desk chair would be found amidst the paraphernalia of a professional’s equipage: a pipe, a magnifying glass, a pocket watch, some butterfly specimen and an emerald green desk lamp, an expensive fountain pen and even more expensive culinary delicacies such as lobster and oysters, all set against a black and white floor, a hefty wooden desk, rich damask green wallpaper, verdant plant life and a floor to ceiling window view of the Paris chimneys beyond. And of course, because it’s Paris, the Gentleman has to keep up with the French news in Le Figaro. Meanwhile at the heart of the image, representations of the Gentleman himself: his top hat, a bowtie and wing-collared shirt, and his face, masked in the enigmatic disguise of a masquerade ball.

Explaining this painting is a little like explaining one’s impulses. This is an image which came to my mind in Spain which always provides me with sufficient relaxation and creative stimulation to get my artistic juices running. And even though the resulting painting is far from Spanish, it nonetheless digs deep in my imagination, placing on canvas a time, a place with which I can feel an inexplicable evocation, like an experience which recalls the strongest of emotions, even though it never happened. In this way, I use painting to make sense of the deepest of subconscious sentimentality, helping me to both explore myself, and pay homage to the depth of my creativity.

I leave you with a few shots of the painting’s details. I hope you like it.

© Nicholas de Lacy-Brown and The Daily Norm, 2001-2012. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of the material, whether written work, photography or artwork, included within The Daily Norm without express and written permission from The Daily Norm’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Nicholas de Lacy-Brown and The Daily Norm with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.