War on film: War Horse v Pan’s Labyrinth

War is in vogue right now – ok, not literally – but dramatisations of the first world war, or “The Great War” as it became known (with no appreciation of the horrors which were to come with the second) are popping up all over our screens. Here in the UK we had the depiction of the trenches in the now Golden-Globe winning period drama, Downton Abbey, where war even encroached upon the aristocrats’ much prized drawing room as the great stately mansion was turned over into a pop-up hospital – perish the thought. Meanwhile, I am chaffing at the bit with excitement as I anticipate the forthcoming television adaptation of Sebastian Faulkes’ Birdsong – surely one of the best fictional portrayals of war ever written, and the first book (and the last) which has ever made me cry. In the theatres, the West End blockbuster, War Horse, adapted from the children’s book by Michael Morpurgo, has been the talk of town, selling equally well when it moved over to Broadway. And now, finally, the WW1 frenzy has moved to our cinemas, as the very same equestrian sensation of War Horse hits our screens thanks to it’s overhaul and adaptation by the one and only, Steven Spielberg.

So, caught up in the excitement, I trotted along to the cinema to see War Horse on the first day of its general release. This was after the popular press spoke of a masterpiece, a tear jerker – by god, even the Duchess of Cambridge had been crying at the Royal premier in London – Speilberg’s best work for years and so on. And indeed I went along with high expectations. After all, wasn’t it Spielberg who directed that emotive, black and white masterpiece that is Schindler’s List and the equally powerful Saving Private Ryan? Sure, Spielberg has had his tacky moments – I’m thinking E.T. on a bicycle riding off as a silhouette in front of the moon, gigantic dinosaurs doing what ever they do in Jurassic Park (I can’t say I’ve ever watched more than about 10 minutes of this franchise) and the plastic shark in Jaws 1 – but with the likes of Schindler he’s directed some pretty stunning, serious masterpieces. But with War Horse Spielberg does not recreate his previous war-themed genius. He certainly does recall his tendency for directing tacky, sensationalised Hollywood tack which makes you cry indeed – from desperation.

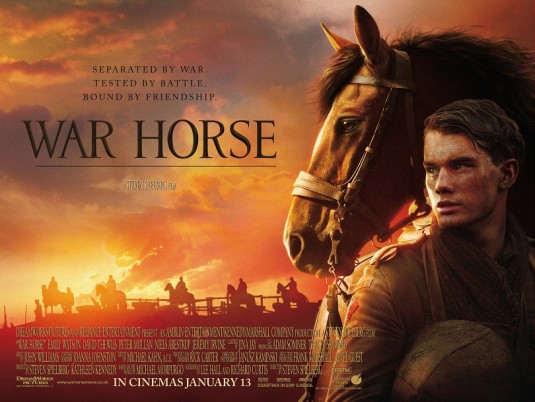

Call me a cynic, but this poster says it all. Horse and man, stood together, hair tussled in the wind, the warm glow of a sunset reflecting on their faces which are absorbed in ambient pouting heroism. And from the cliched blockbuster poster follows a film which is overloaded with contrived, cheesy banality and boring, over-acted scenes which stretch the film to it’s full almost three-hour painstaking duration.

The problems with the film are several: Its central character is a horse, and it’s all about people who love horses. And if you don’t love horses, or go gooey over animals, you won’t enjoy this film. It’s like being forced to look at a hundred photos of your friend’s beloved dog in various subtly altered positions, trying to show enthusiasm in someone else’s passion when all you want to do is vomit into your wineglass. The next issue is the banality of the screenplay. There is a scene mid-film when a young French girl starts talking to the horses about the boys she fancies at school. It was at that point I started panicking desperately in my cinema seat, wondering how the hell I would escape this torture seeing as, about 90 minutes through, there was still no sign of full-scale war. Then there’s the sensationalist, unrealistic and utterly Hollywood manufactured scenery – a British village, so idealised and peach-tinted that it felt like the image from a perfumed pin-cushion purchased from a National Trust gift shop – or the final scene when the characters meet, silhouetted in a silent embrace against a sunset, silhouetted that is until Joey the horse turns towards the camera, the sunshine reflected in his gleaming coat, a twinkle in his eye. Oh god, it makes me shiver just to recollect it. And then there’s the soundtrack. It has one of those terribly grandiose musical scores which is supposed to be rousing, but which tries to supplant your emotional responses with its own pockets of dramatic rise and fall. So Gone with the Wind and just so overdone.

So what’s good about it? Well hats go off to Spielberg on two accounts: First the scene (shown above) when Joey the Horse is shown running through the trenches, across no man’s land, avoiding explosion, pit-holes, stagnant ponds and gunfire, until the poor horse gets caught up in barbed wire. The graphics in this scene are superb – although Spielberg has clearly garnered inspiration for his WW1 portrayal from the masterpiece illustrations of war by British artist Paul Nash. His great painting – The Menin Road – looks almost identical to the Speilberg set.

The second plaudit has to go to Spielberg’s inspired and intelligent portrayal of the shooting of two German boys who were deserting from service. In the shadow of a great windmill in the French countryside we see the boys standing one second, and shot down with the passing of the windmill sail. This, I thought, was a very poignant moment in the film, and saves us the horror of seeing two young boys killed and point blank range, while retaining all the potency of their premature deaths.

Now you may think that my review above is unduly harsh, but the problem is, I went to see this film only one day after seeing the Mexican director, Guillermo del Toro’s cinematic masterpiece, Pan’s Labyrinth (“El laberinto del fauno”). While screened in late 2006, I only came across this film recently and promptly purchased it on DVD. Expecting a fantasy animation, and excited by the foreign language element, I was very, very pleasantly surprised by a film which tackles the subject of horrifying war in the most original of ways. Now this is what War Horse should have done.

Now you may think that my review above is unduly harsh, but the problem is, I went to see this film only one day after seeing the Mexican director, Guillermo del Toro’s cinematic masterpiece, Pan’s Labyrinth (“El laberinto del fauno”). While screened in late 2006, I only came across this film recently and promptly purchased it on DVD. Expecting a fantasy animation, and excited by the foreign language element, I was very, very pleasantly surprised by a film which tackles the subject of horrifying war in the most original of ways. Now this is what War Horse should have done.

The film is set in the immediate aftermath of the Spanish Civil War. Although Franco’s fascists had largely won the war, pockets of resistance remained, resistance which held on for the duration of the second world war in the hope that the Allies would help to defeat Franco after the war. Sadly this never happened, and it is with this feeling of hopelessness that one watches scenes of horrific violence and horror, knowing that this was the regime which not only won the war, but ruled Spain for a further 35 years. The film centres around the Falangist Captain Vidal who has relocated to a rambling old Mill in the Northern forested province of Navarra in order to hunt out the resistance there. Two spoils of his victory are his new wife, Carmen, and her daughter, Ofelia, who are forced to move to the house so that Vidal can witness the birth of his awaited son so that he can affirm and celebrate the birth of his first descendant in Franco’s Spain.

The film is largely shown through the eyes of Ofelia who, upon discovering an ancient labyrinth, enters a strange mystical world where, led on by the faun who gives the film it’s name, she is set several fantastical but gorey challenges in the hope of obtaining immorality. These mystical adventures run in jarring, contrasting parallel to the stark realities of murderous and gratuitous violence executed at the hand of Captain Vidal and his men, but interestingly, as Ofelia is progressively exposed to the horrors of her surroundings, you see that her escapism into a magical world leads her into situations which are more and more dangerous and desperate. This all leads up to the end of the film, where the two worlds collide with devastating results, and you quickly realise that the scenes of fantasy were Ofelia’s imagined way of escaping from, and dealing with the horrors all around her.

The film is largely shown through the eyes of Ofelia who, upon discovering an ancient labyrinth, enters a strange mystical world where, led on by the faun who gives the film it’s name, she is set several fantastical but gorey challenges in the hope of obtaining immorality. These mystical adventures run in jarring, contrasting parallel to the stark realities of murderous and gratuitous violence executed at the hand of Captain Vidal and his men, but interestingly, as Ofelia is progressively exposed to the horrors of her surroundings, you see that her escapism into a magical world leads her into situations which are more and more dangerous and desperate. This all leads up to the end of the film, where the two worlds collide with devastating results, and you quickly realise that the scenes of fantasy were Ofelia’s imagined way of escaping from, and dealing with the horrors all around her.

This film is such an imaginative way of portraying war, and I was completely stunned by its originality and creativeness. In as much as it shocks, it does so sending home a firm message that the Spanish Civil War was a time of abject horror; a time which, despite the attempts of two generations of Spaniards, should not, and never can be forgotten. By contrast, War Horse was cliched and unoriginal, and having focused its attention on the relationship of man and horse and, worse, the love between two horses, it somewhat distracts from the true horror of the Great War and the very great sacrifice which was made by millions of men…and horses.

Related articles

- Spielberg’s War Horse Moves Kate Middleton To Tears (lukewilliamss.wordpress.com)

So I have to say, while I appreciated the things you have to say on both movies, I have to ask, do you think it is fair to compare these two movies with each other? I mean, yes they are both movies and yes they both involve war, but I’m not sure we are comparing apples to apples. Granted I haven’t seen War Horse (and thanks to your critique I will be saving my $10), but Pan’s Labyrinth seemed less about the war and more about a child and her perceptions of the world and her inability to cope with the changes she is faced with. I did enjoy your insights about the movie though. Good stuff.

Hey Farheen, many thanks for your comment and for paying such close attention to my review – really appreciated! I guess it is a little unfair to compare the films in a like for like fashion, but by way of broad comparison I think that Pan’s Labyrinth demonstrated an originality in the portrayal of war which Spielberg’s film totally lacked – his film was so chocolate box cliche that you could have wrapped it up with a ribbon. The problem was, I had watched Pan’s Labyrinth the night before War Horse – by complete coincidence – and therefore what I am saying in my post is that I can’t help but compare them, because one was still very vivid in my mind when I watched the other. Having said all that, while I agree Pan’s Labyrinth does explore a child’s perceptions of the world around her, I do think that her fantastical imaginings, in their dark and sinister manifestation, were a direct and paralleled reflection of the violent, horrendous post-war world around her. In the same way, War Horse explores the subject of WW1 through a young boy’s relationship with his horse – I gather in the original book, the story may even have been told from the horse’s perspective (although I haven’t read it). In this way, both films are an original perspective on war – it’s just that Spielberg’s direction – the music, cinematography and so on – was, I thought, intrinsically unoriginal. Thanks again for reading and for your perspective! Please keep the comments coming!