Bored of the Pre-Raphaelites? Head straight to William Morris

The problem with the Pre-Raphaelites, the brotherhood of artists formed in England in 1984 by founding members John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti and William Holman Hunt, is that they have become a British institution. As much an institution in fact as the Queen’s corgis, the black cab and Big Ben. And like many a British institution, they get carted out, every so often, more often than not when times are down, when blockbuster exhibitions are expensive to organise, and its cheaper to take the best of British out of the closet. So seems to be the case with Tate Britain’s new “blockbuster” show, Pre-Raphaelites: Victorian Avant-Garde, which promises to be a re-examination of the PRB, but in actual fact presents us with the same old paintings, the same old themes, and the same old narrative that we have seen time and time again.

Now don’t get me wrong. I’m not saying that these paintings aren’t good – they are in fact pretty incredible, packed with their flowing fantastical red locks, the precision of Millais’ plants and flowers, the scale of their pictorial ambition and the brilliance of their life-like representation within a mystical setting. It’s just that even the most incredible painting can lose its gleam when it’s seen time and time again. In the last 5 years alone, Tate gave us a Millais retrospective (Sept 2007-Jan 2008) and a Romanticism display (Aug 2010-April 2012), centred around Pre-Raph favourites. Meanwhile at the Royal Academy, we had a retrospective of that other PRB favourite, J W Waterhouse (June-Sep 2009), and at the V&A the same old brotherhood was featured heavily in the exhibition on Aestheticism (April-July 2011). And so you see, with Tate’s new show, which promises to give us something new, and really doesn’t, it’s all a bit, well, underwhelming.

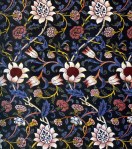

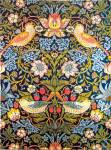

Skip through 6 rooms however, and in the room named “paradise” you really do get something worth visiting. For in showing the designs of William Morris, now famous for his Victorian fabrics which have become equally and intrinsically part of the “fabric” of British society (excuse the pun), you get to see these much loved designs in a new light – works which, when placed in a gallery setting, take on a new life force, as the viewer is encouraged to appreciate the intricacies of the designs and the decadent elegance of the period from which they arise. The Morris display did, admittedly, come as something of a surprise – Tate justifies its inclusion on the rather tenuous basis that Morris had been inspired by the PRB (as well as the medieval past, with which the PRB artists were also rather enamoured) in embarking upon his designs. Oh, and apparently Rossetti and a few other artists of the time were partners in Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co, the company which started producing the now widely-recognised fabrics on an almost industrial scale.

Whatever the connection, I was glad for it – Morris’ designs were my favourite part of the show and, although sparse in number, made me realise how often undervalued Morris is in art history. Too often overlooked as a designer, or at best an illustrator, are not these beautifully hand-crafted designs every bit as valid as artistic masterpieces as a Millais painting? Of course the art or illustration debate has gone on for years, and god knows, I have often been “accused” of being more an illustrator than an artist myself. But call it what you like – I’d far rather admire these “designs” in an art gallery than a filthy Tracey Emin bed any day.

I leave you with some of Morris’ best.

In the meantime, if you can stand the repetition, Pre-Raphaelites: Victorian Avant Garde is on at Tate Britain, London, until 13 January 2013.

Related articles

- Pre-Raphaelites: Victorian Avant Garde (madameguillotine.org.uk)

- Brian Sewell on Pre-Raphaelites: Victorian Avant-Garde at the Tate Britain (standard.co.uk)