Norms do…Goya – The Third of May 1808

When people think about paintings of conflict, the first name to pop into their head is generally Guernica. The painting, by Picasso, has become a worldwide antiwar symbol, and as if proving the fact, a large tapestry of the painting hangs outside the UN’s Security Council HQ in New York (you know, the same one that they covered up with curtains when making the decision to go to war against Iraq). But in actual fact, there was painted, some 120 years earlier, an equally striking image of conflict, sacrifice and war, an image so resonant, in fact, that Picasso cited it as an inspiration to his Guernica. The painting is The Third of May 1808, by Francisco Goya.

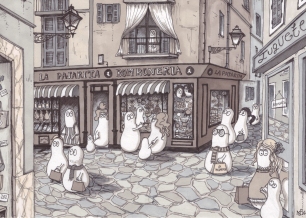

As my regular readers will have twigged, I’m a big fan of Spanish art, and therefore it is no surprise that somewhere in the dark depths of my imagination, a Norm version of Goya’s magnum opus would take its form, emerging as a brief watercolour sketch the other night. Here it is, with Goya’s original masterpiece.

To give a brief background, Goya’s work represents an uprising of Madrid residents in response to the French invasion of Spain under Napoleon I. Having tricked the Spanish into an alliance with the French armies with a view to conquering Portugal and splitting it between then, Napoleon entered Spain with his armies in November 1807 under the guise of strengthening Spanish troops. However, having entered Spain, Napoleon’s true intentions were unveiled, and the French troops moved in to take control of the country, facing very little resistance. It was only on 2 May 1808, when the people of Madrid learnt that the Spanish royals were to be exiled to France, that many of them rose up in rebellion against the French troops. The French army ultimately prevailed, but not without great bloodshed, and Marshal Murat, head of the French army in Spain declared: “The population of Madrid, led astray, has given itself to revolt and murder. French blood has flowed. It demands vengeance. All those arrested in the uprising, arms in hand, will be shot.”. Goya’s painting depicts the moment, early the next morning, when hundreds of Spaniards were led from the monastery where they had been imprisoned overnight (probably the buildings shown in the background) to the surrounding barren lands where they faced point-blank execution before a firing-squad.

The Second of May 1808 by Francisco Goya (1814), courtesy of the Prado, Madrid - partner of the Third of May, this painting depicts the uprising itself.

Goya’s painting is a stunning symbol of slaughter and sacrifice. It works so well on so many levels. There is, for example, the haphazard grouping of sacrificial victims on the left, a monk-like figure shown bending to meet his fate, others turning away in despair, the blood of innocents all over the floor, bloody corpses foreshortened as though falling into the space of the audience. The group of victims shows a human, unorganised element which compares effectively with the group of gunmen on the right who are rigid, dark, sinister, grouped together like a killing machine showing no remorse or sway in their murderous resolve. This contrast of dark and light creates a wonderful tension – good versus evil. Of course the most striking character is the central victim, dressed in a glowing white, his colours matching those of the lantern which casts light upon the scene. Shown with his arms outstretched, he is a christ like figure – he even appears to have the marks of stigmata upon his hands – all suggesting that he represents those Spaniards who stood up to the French invaders, sacrificing their lives for the sake of ultimate Spanish victory. It’s a work which portrays bloody human waste – a waste of life, the destruction of the innocents – and this is why it still stands today as such a powerful anti-war symbol.

Unsurprisingly the painting has inspired countless artists since it went on display in a rather pokey corner of the Prado (after it lay in storage for 40 years – the King of the time, Ferdinand VII, didn’t like it as it glorified people rather than him). One of the first interpretations of the image was this one, by Édouard Manet, which depicts the execution of Emperor Maximilian of Mexico.

Maximilian, a member of the Hapsburg family of Austria, had been installed in power in Mexico by Napoleon III of France in an attempt to recover unpaid debts and establish a European presence there. This endeavor failed, ending with the execution of Maximilian and two of his generals by firing squad on 19th June 1867. Here, the emphasis is reversed, as Manet, ever anti-Napoleon, makes the executors the heroes of the piece, dressed in their smart livery, whereas Maximilian and his generals are, by contrast, depicted with dark, undefined, sinister brushstrokes.

The second most significant use of Goya’s composition is Massacre in Korea by Picasso which depicts the Sinchon Massacre, an act of mass killing carried out by the South Korean and/or American forces in 1950.

Here the firing squad are once again the aggressors, and Picasso has taken the idea of the killing machine to a new level, depicting the squad as a fantastical group of sinister, mechanical automatons, killing without emotion of any kind. By contrast, the victims are as emotive as could be depicted – women and children, one seemingly pregnant, another’s face crippled with despair.

A final, lesser-known depiction, is the pop art homage painted by Irish artist, Robert Ballagh.

Entitled The Third of May 1970, the painting makes a direct reference to Goya’s work, making no changes to the composition whatsoever, but converting the work into a pop-art creation using black outlines and block colours. The 1970 title of the work is intended to reflect another time of great conflict – this time in Northern Ireland – when British troops entered to enforce some semblance of control.

All three depictions serve demonstrate the continuing relevance of The Third of May 1808 in times of conflict. Like Picasso with his Guernica, Goya created a work for all times, a stark reminder of the brutality and savagery which comes so easily in times of conflict, a brutality which has continued to erupt intermittently around the world, and which, only 120 years after the Third of May, savaged Goya’s homeland, once again.

© Nicholas de Lacy-Brown and The Daily Norm, 2005-2012. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of the material, whether written work or artwork, included within The Daily Norm without express and written permission from The Daily Norm’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Nicholas de Lacy-Brown and The Daily Norm with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Just recently discovered you blog, but I love it. It’s so varied in topics and they’re all interesting. I really liked this post and learned new things too. Thanks!

I agree with Inga

Great article.

I think there is another dimensions in Manet’s painting – the casualness of the executioners and their rounded, almost comical figures.

And the man behind the firing squad doing something workmanlike with his rifle.

And the people on the wall watching – are the appalled, excited? They look more like they are at a fairly interesting public event.

I agree, the audience of fascinated spectators is particularly gruesome, but it says a lot about human nature, what ever else it may say about the politics behind the painting (about which, admittedly, I am not overly informed). Huge thanks for your support and comments. More like that article on their way next week.